Carolyn Thomas, a Canadian writer, Mayo Clinic-trained advocate for women’s heart health and herself a heart attack survivor, observes the parade of self-monitoring and Quantified Selfing by ‘urban datasexuals’ at Stanford University’s Medicine X conference at end of September. Originally published in her blog Heart Sisters.

Shortly after arriving at Stanford University School of Medicine to attend the conference called Medicine X (“at the intersection of medicine and emerging technologies”), it hit me that I didn’t quite belong there. Maybe, I wondered, the conference organizers (like the profoundly amazing Dr. Larry Chu) may have goofed by awarding me an “ePatient Scholarship” – rather than a more tech-savvy, wired and younger patient in my stead.

Shortly after arriving at Stanford University School of Medicine to attend the conference called Medicine X (“at the intersection of medicine and emerging technologies”), it hit me that I didn’t quite belong there. Maybe, I wondered, the conference organizers (like the profoundly amazing Dr. Larry Chu) may have goofed by awarding me an “ePatient Scholarship” – rather than a more tech-savvy, wired and younger patient in my stead.

Please don’t get me wrong – I was and still am duly thrilled and humbled to be chosen as one of 30 participants invited to attend MedX as ePatient scholars, generously funded by Alliance Health after we met selection criteria like “a history of patient engagement, community outreach and advocacy”.

But almost immediately, I started feeling like a bit of a fraud…

At Medicine X, the entire first day’s agenda, for example, focused on the concept of self-tracking. Mobile technology means we can now whip out a smartphone to keep track of our weight, our mood, our sex life, the food we eat, how much we exercise, how well we sleep, or the number of computer keystrokes we rack up each day.

The MedX conference kickoff speaker on self-tracking was the delightful Susannah Fox, Associate Director of Digital Strategy at Pew Internet and American Life Project, a self-described “internet geologist.” Susannah made me feel a bit better by pointing out her own favourite self-tracking tool – the skinny jeans in her closet.

Every woman knows that one’s skinny jeans represent an accurate (albeit low-tech) weight assessment tool. And maybe skinny jeans are indeed every bit as useful as tracking weight on a smartphone health app like DailyBurn, or on Fitbit’s Aria Wi-Fi Smart Scale. The latter can not only weigh you, but can then post your scale numbers directly online to your Twitter followers. (This, by the way, might just be the health app equivalent of tweeting your morning Starbucks order to followers who apparently are desperately interested in your every waking moment).

There’s an entire ‘Quantified Self’ movement of hobbyists who enjoy tracking what they’re thinking or what they’re doing or what they’re thinking about doing, a number of whom we heard from at MedX. Quantified Selfers have a website, they plan meetups, and apparently had a swell time at last month’s annual conference (also in Palo Alto) sharing many trackable details about themselves that could possibly make your head explode if you are not a bona fide Quantified Selfer. Conference highlights included self-tracking reports on things like caffeine intake, heart rate, cognitive skills, geographic location, facial expressions, hydration levels, money saved/spent, ambient noise level, light exposure and vocabulary size.

According to their website, most QS types are male. Some have health issues they are keeping track of (diabetics who monitor their blood test results, for example) but many do not.

My overall observation at MedX – and one that I did not hear addressed by any of the conference speakers – was that there’s likely a big fat difference between the highly engaged community of technology mavens who enthusiastically track their personal data just because they can, and actual real live sick people living with serious chronic disease every day who lack the energy/ability/will to commit to self-tracking in any kind of meaningful fashion.

I am one of them. I consider myself an engaged patient, but I do not own a smartphone, a 7-inch tablet, or an iPad–nor, as a person with a chronic illness living on a disability pension, could I afford them. One wonders if anybody in the QS world or in health care tech startup companies is even remotely aware that there are actually patients like me out there?

(And speaking of startups, does everybody in Palo Alto own one? Even the kid on the bus who was our Silicon Valley Tech Tour guide – a fourth year Stanford student – has his own startup, for Pete’s sake!)

Pew Internet’s own studieson the general online activities of people living with a disability suggest that those who are most likely to be diagnosed/living with chronic disease/disability may indeed be least likely to turn to technology to enhance health outcomes. For example:

- One in four adults live with a disability that interferes with activities of daily living.

- Disability is associated with being older, less educated, and living in a lower-income household.

- 58% of disabled patients are age 50 or older.

- Internet use is statistically associated with being younger, college-educated, and living in a higher-income household.

- Just 54% of adults living with a disability use the internet, compared with 81% of adults who report none of the disabilities listed in PEW surveys.

- Only 13% of those ages 65 and older own a smartphone.

In another report published in Journal Watch Emergency Medicine, a disturbing number of Chicago patients being discharged from hospital with both oral and written care instructions do not understand their discharge instructions. While the tracking technology folks featured at MedX may view such patients as a potential target market ripe for the picking, researchers describe “a worrisome deficit in patients’ understanding of how to care for their illness at home and in what circumstances they should return to the Emergency Department”.

Why would we suddenly believe that patients like these will somehow adopt emerging health technology when they cannot/do not comprehend “individualized in-person discharge instructions as well as written instruction sheets specific to their discharge diagnosis”?

And as Donna Cusano (who casts The Gimlet Eye on health technology over at the Telecare Aware site) wrote: “Quantified Selfers are totally unconscious of the fact that the market which can most use a tracking system is the least likely to use one!”

David Whelan of Forbes turned his own gimlet eye on the hype-meisters of health care tech startups who “overpromote into a stratospheric hype zone of self-importance”. Their technology, warns Whelan, “will not help fix the health care system” – despite the claims of those paid to promote it. He adds: “It’s true that you can point a finger at health care and say it lacks technology. But it’s not because the tech doesn’t exist. It may be that technology doesn’t really fit.”

The Next Big Thing in emerging technology might have nothing to do with health care at all, according to The Wall Street Journal’s 2012 ranking of the top 50 venture-capital-backed companies – the first year that a health care company did not top the ranking. For example, last year’s WSJ list-topper (Castlight Health Inc.) dropped out of the top 50 entirely as “the health care industry in general has fallen out of favor with venture capitalists.” There was a very large elephant in the Stanford University conference rooms at the Medicine X conference, and it’s only now that I have recovered enough to raise one tentative hand in the air to interrupt the self-congratulatory high-fives of health tech insiders – the so-called urban datasexuals (whom I’ve previously written about on my other site, The Ethical Nag: Marketing Ethics for the Easily Swayed).

Here’s an example: one self-tracker reported his gee-whiz revelation that traffic jams and meetings raise his stress level – this according to his wristwatch sensor that monitors heart rate and overlays said data on his Outlook calendar. Please note: I would have willingly told him that for free before he shelled out $200 for the new watch.

Consider also the example of Larry Smarr, a very sharp astrophysicist with a background in supercomputing and founder of the Calit2 research centres located at both UC San Diego and UC Irvine. He’s been a committed self-tracker for about five years. Larry recently told an Orange County Register interviewer that he wears a Fitbit and Zeo on a daily basis, and a heart rate monitor when exercising. He also analyzes his own stool samples – I am not making this up! – by freezing and then sending them off to labs to investigate the contents, all in the pursuit of science and insights about his own fascinating self. [TA 16 Aug] The trouble is, Quantified Selfers like Larry may give the casual observer reason to suspect that they are somehow living at the intersection of geekdom and nerdville.

Or, as Telecare Aware’s Donna Cusano more bluntly concludes: “The self-absorption of some QS adherents has a whiff of stark raving narcissism about it all.”

Then there’s Massachusetts physician, author, researcher and UMass professor of epidemiology Dr. Marya Zilberberg who has observed: “The self-monitoring movement is just another manifestation of our profound self-absorption. When you measure something, presumably you have to react to it. Is the hope that this constant self-monitoring will change our behavior? Just look at how decades of focus on diets and weight have fared. In fact, it feels to me that this fixation on blow-by-blow narrative of our ‘health’ is quite the opposite of what real health looks like.”

And as one MedX attendee mused on Twitter: “Why do we think self-tracking health devices will work when mirrors and bathroom scales have so far failed?”

Besides, for the average person (e.g. those who are not astrophysicists with a keen interest in collecting and analyzing their own stool samples), we know that only 5% of mobile phone applications – including health tracking apps – are still in use 30 days after downloading.

Aside from the tech-savvy participants at Medicine X, self-tracking seems to be so far largely limited to early adopters: technophiles, elite athletes and patients monitoring chronic health conditions.

As a dull-witted heart attack survivor, I’m most interested in this third group. Yet paradoxically, I’m also realistically cynical about this group’s wholesale adoption of self-tracking. I see significant challenges in convincing people like me who are living with a debilitating chronic illness to somehow embrace technology as their digital saviour.

Dr. Joseph Kvedar, a physician and founding director of the Center for Connected Health at Harvard Medical School, believes that physicians need to turn “as many of our patients as possible into Quantified Selfers” – but he has also candidly admitted some of the very real challenges in doing so. He describes the gulf between Quantified Selfers and average patients like me: “One explanation could be that managing chronic disease can be complex and too overwhelming for some patients to take on anything more.”

Thus Dr. K exquisitely grasps what many Quantified Selfers do not.

While individual outliers may have enthusiastically embraced the self-tracking trend (we heard many of these patients and doctors onstage at MedX), the reality is that many more have not and will not. As a heart attack survivor with ongoing cardiac issues, I call this the “One Damned Thing After Another” phenomenon, when simply taking out the recycling bin can feel like far too much for me to manage on a bad day.

How are health tech startups planning to address this particular demographic? Or are they even going to bother?

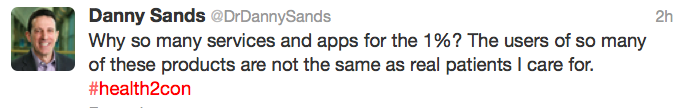

It’s health care conference season out there, and techies are showing off their wares in full force – not just at Medicine X at Stanford. For example, at San Francisco’s Health 2.0 conference this week, Dr. Danny Sands (founder and former president of the Society for Participatory Medicine) just tweeted this:

And as one similarly concerned physician said to me while watching yet another particularly enthusiastic demo of yet another life-changing tracking app during MedX: “Are these Quantified Selfers talking about real patients?”

P.S. to Dr. Larry Chu: Lest I appear to be an ungrateful Luddite – ooops, too late! – I would like to add my sincere appreciation for the opportunity to visit your beautiful university, to marvel at the kindness and hospitality of your whole Stanford AIM team in organizing a medical conference unlike any other, to meet so many committed health care professionals from all over the world who view patients as true partners in our journey together, and to witness with my own eyes so many inspired and inspiring patients included onstage, in the audience and at the microphones. Thank you for this!

You can watch video highlights of the Medicine X conference sessions via this Open Access Program.

Thanks so much for reposting my “elephant” article here on your Soapbox!

Regards,

C.

Thank you so much for posting this article. The term ‘datasexuals’ suckered me in and a heartier, funnier informative read I have not had in a long while (50 Sades of Grey excluded) that peice is sending me off to work with a smile on my face. Unfortunately my freezer is full so I don’t need to resist the temptation of freezing a stool sample, though look out for my tweet when I arrive at Starbucks later!

A most enjoyable read….and I mostly agree with you. And thx for adding to my dictionary of TLAs (two/three letter abbreviations!) – QSs are indeed a niche.

We always say ‘healthcare first, technology second’. Telestealth is the word we use internally when we talk to our techie teams – patients want things that are easy to use and just work. If it creates hassle then it won’t be used….if you have chronic pain or are breathless then just how much energy have you got to get through the day? We deliver healthcare services to the ‘hardly reached’ and certainly we don’t expect them to have smart phones … but we know that the ‘hardly reached’ do share electronic consumer goods between the larger family groups. So very cheap basic mobile phones and a PC is normally available in a family cohort….and we also know and have experienced the young in the family helping the older ones.This is not the case all the time but at least there are avenues for some of the ‘hardly reached’ to access healthcare services where they are not normally used.

We try and keep our feet on the ground .. the start-ups find this difficult to do.

A great read. Larry Smarr brings a whole new way of my mind saying the word ‘Analysis’.

Those who need these systems and apps won’t get them because they are not engaged enough or don’t see the benefits of them to want them.

The worried well will have them but not need them.

We need to Nanny McPhee the hell out of the former.